Ever since the arrival of the first Europeans in the New World, Peyote has provoked controversy, suppression, and persecution. Condemned by the Spanish conquerors for its "satanic trickery", and attacked more recently by local governments and religious groups, the plant has nevertheless continued to play a major sacramental role among the Indians of Mexico, while its use has spread to the North American tribes in the last hundred years. The persistence and growth of the Peyote cult constitute a fascinating chapter in the history of the New World - and a challenge to the anthropologists and psychologists, botanists and pharmacologists who continue to study the plant and its constituents in connection with human affairs. THE TRACKS OF THE LITTLE DEER

from

Plants of the Gods -

Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers

by Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hoffman

Healing Arts Press (Vermont) 1992We might logically call this woolly Mexican cactus the prototype of the New World hallucinogens. It was one of the first to be discovered by Europeans and was unquestionably the most spectacular vision-inducing plant encountered by the Spanish conquerors. They found Peyote firmly established in native religions, and their efforts to stamp out this practice drove it into hiding in the hills, where its sacramental use has persisted to the present time.

How old is the Peyote cult? An early Spanish chronicler, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, estimated on the basis of several historical events recorded in Indian chronology that Peyote was known to the Chichimeca and Toltec at least 1890 years before the arrival of the Europeans. This calculation would give the "divine plant" of Mexico an economic history extending over a period of some two millennia. Then Carl Lumholtz, the Danish ethnologist who did pioneer work among the Indians of Chihuahua, suggested that the Peyote cult is far older. He showed that a symbol employed in the Tarahumara Indian Peyote ceremony appeared in ancient ritualistic carvings preserved in Mesoamerican lava rocks. More recently, archaeological discoveries in dry caves and rock shelters in Texas have yielded specimens of Peyote. These specimens, found in a context suggesting ceremonial use, indicate that its use is more than three thousand years old.

The earliest European records concerning this sacred cactus are those of Sahagún, who lived from 1499 to 1590 and who dedicated most of his adult life to the Indians of Mexico. His precious, first-hand observations were not published until the nineteenth century. Consequently, credit for the earliest published account must go to Juan Cardenas, whose observations on the marvelous secrets of the Indies were published as early as 1591.

Sahagún's writings are among the most important of all the early chroniclers. He described Peyote use among the Chichimeca, of the primitive desert plateau of the north, recording for posterity: "There is another herb like tunas [Opuntia spp.] of the earth. It is called Peiotl. It is white. It is found in the north country. Those who eat or drink it see visions either frightful or laughable. This intoxication lasts two or three days and then ceases. It is a common food of the Chichimeca, for it sustains them and gives them courage to fight and not feel fear nor hunger nor thirst. And they say that it protects them from all danger."

It is not known whether or not the Chichimeca were the first Indians to discover the psychoactive properties of Peyote. Some students believe that the Tarahumara Indians, living where Peyote abounded, were the first to discover its use and that it spread from them to the Cora, the Huichol, and other tribes. Since the plant grows in many scattered localities in Mexico, it seems probable that its intoxicating properties were independently discovered by a number of tribes.

Several seventeenth-century Spanish Jesuits testified that the Mexican Indians used Peyote medicinally and ceremonially for many ills and that when intoxicated with the cactus they saw "horrible visions". Padre Andréa Pérez de Ribas, a seventeenth-century Jesuit who spent sixteen years in Sinaloa, reported that Peyote was usually drunk but that its use, even medicinally, was forbidden and punished, since it was connected with "heathen rituals and superstitions" to contact evil spirits through "diabolic fantasies".

The first full description of the living cactus was offered by Dr Francisco Hernández, who as personal physician of King Philip II of Spain was sent to study Aztec medicine. In his ethnobotanical study of New Spain, Dr Hernández described "peyotl", as the plant was called in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs: "The root is of nearly medium size, sending forth no branches or leaves above the ground, but with a certain woolliness adhering to it on account of which it could not aptly be figured by me. Both men and women are said to be harmed by it. It appears to be of a sweetish taste and moderately hot. Ground up and applied to painful joints, it is said to give relief. Wonderful properties are attributed to this root, if any faith can be given to what is commonly said among them on this point. It causes those devouring it to be able to foresee and to predict things…."

In the latter part of the seventeenth century, a Spanish missionary in Nayarit recorded the earliest account of a Peyote ritual. Of the Cora tribe, he reported: "Close to the musician was seated the leader of the singing, whose business it was to mark time. Each had his assistants to take his place when he should become fatigued. Nearby was place a tray filled with Peyote, which is a diabolical root that is ground up and drunk by them so that they may not become weakened by the exhausting effects of so long a function, which they begin by forming as large a circle of men and women as could occupy the space that had been swept off for this purpose. One after the other, they went dancing in a ring or marking time with their feet, keeping in the middle the musician and choir-master whom they invited, and singing in the same unmusical tune that he set them. They would dance all night, from five o'clock in the evening to seven o'clock in the morning, without stopping nor leaving the circle. When the dance was ended, all stood who could hold themselves on their feet; for the majority, from the Peyote and wine which they drank, were unable to utilize their legs."

The ceremony among the Cora, Huichol, and Tarahumara Indians has probably challenged little in content over the centuries; it still consists, in great part, of dancing.

The modern Huichol Peyote ritual is the closest to the pre-Colonial Mexican ceremonies. Sahagún's description of the Teochichimeca ritual could very well be a description of the contemporary Huichol ceremony, for these Indians still assemble together in the desert 300 miles northeast of their homeland in the Sierra Madre mountains of western Mexico, still sing all night, all day, still weep exceedingly, and still so esteem Peyote above any other psychotropic plant that the sacred mushrooms, Morning Glories, "Datura", and other indigenous hallucinogens are consigned to the realm of sorcerers.

Most of the early records in Mexico were left by missionaries who opposed the use of Peyote in religious practice. To them Peyote had no place in Christianity because of its pagan associations. Since the Spanish ecclesiastes were intolerant of any cult but their own, fierce persecution resulted. But the Indians were reluctant to give up their Peyote cults established on centuries of tradition.

The suppression of Peyote, however, went to great lengths. For example, a priest near San Antonio, Texas, published a manual in 1760, containing questions to be asked of converts. Included were the following: "Have you eaten the flesh of man? Have you eaten Peyote?" Another priest, Padre Nidolas de Leon, similarly examined potential converts: "Art thou a soothsayer? Dost thou foretell events by reading omens, interpreting dreams or by tracing circles and figures on water? Dost thou garnish with flower garlands the places where idols are kept? Dost thou suck to blood of others? Dost thou wander about at night, calling upon demons to help thee? Hast thou drunk Peyote or given it to others to drink, in order to discover secrets or to discover where stolen or lost articles were?"

During the last decade of the nineteenth century, the explorer Carl Lumholtz observed the use of Peyote among the Indians of the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico, primarily the Huichol and Tarahumara, and he reported on the Peyote ceremony and on various kinds of cacti employed with "Lophophora williamsii" or in its stead.

However, no anthropologist ever participated in or observed a Peyote hunt until the 1960s, when anthropologists and a Mexican writer were permitted by Huichols to accompany several pilgrimages. Once a year, the Huichols make a sacred trip to gather Hikuri. The trek is led by an experienced "mara'akame" or shaman, who is in contact with Tatewari (Our grandfather-fire). Tatewari is the oldest Huichol god, also known as Hikuri, the Peyote-god. He is personified with Peyote plants on his hands and feet, and he interprets all the deities to the modern shamans, often through visions, sometimes indirectly through Kauyumari (the Sacred Deer Person and culture hero). Tatewari led the first Peyote pilgrimage far from the present area inhabited by the nine thousand Huichols into Wirikuta, an ancestral region where Peyote abounds. Guided by the shaman, the participants, usually ten to fifteen in number, take on the identity of deified ancestors, as the follow Tatewari "to find their life".

The Peyote hunt is literally a hunt. Pilgrims carry tobacco gourds, a necessity for the journey's ritual. Water gourds are often taken to transport water back from Wirikuta. Often the only food taken for the stay in Wirikuta is tortillas. The pilgrims, however, eat Peyote while in Wirikuta. They must travel great distances. Today, much of the trek is done by car, but formerly the Indians walked some two hundred miles.

The preparation for gathering Peyote involves ritual confession and purification. Public recitation of all sexual encounters must be made, but no show of shame, resentment, or jealousy, nor any expression of hostility, occurs. For each offense, the shaman makes a knot in a string which, at the end of the ritual, is burned. Following the confession, the group, preparing to set out for Wirikuta - an area located in San Luís Potosí - must be cleansed before journeying to paradise.

Upon arriving within sight of the sacred mountains of Wirikuta, the pilgrims are ritually washed and pray for rain and fertility. Amid the praying and chanting of the shaman, the dangerous crossing into the Otherworld begins. This passage has two stages: first, the Gateway of the Clashing Clouds, and second, the opening of the Clouds. These do not represent actual localities but exist only in the "geography of the mind"; to the participants the passing from one to the other is an event filled with emotion.

Upon arrival at the place where the Peyote is to be hunted, the shaman begins ceremonial practices, telling stories from the ancient Peyote tradition and invoking protection for the events to come. Those on their first pilgrimage are blindfolded, and the participants are led by the shaman to the "cosmic threshold" which only he can see. All stop, light candles, and murmur prayers while the shaman, imbued with supernatural forces, chants.

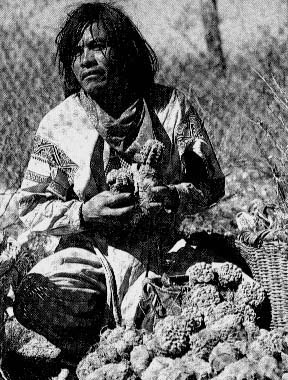

Finally, Peyote is found. The shaman has seen the deer tracks. He draws his arrow and shoots the cactus. The pilgrims make offerings to this first Hikuri. More Peyote is sought, basketfuls of the plant eventually being collected. On the following day, more Peyote is collected, some of which is to be shared with those who remain at home. The rest is to be sold to the Cora and Tarahumara Indians, who use Peyote but do not have a quest.

The ceremony of distributing Tobacco is then carried out. Arrows are placed pointing to the four points of the compass; at midnight a fire is built. According to the Huichol, Tobacco belongs to fire. The shaman prays, placing the Tobacco before the fire, touching it with feathers, then distributing it to each pilgrim who puts it into his gourd, symbolising the birth of Tobacco.

The Huichol Peyote hunt is seen as a return to Wirikuta or Paradise, the archetypal beginning and end of a mythical past. A modern Huichol "mara'kame" expressed it as follows: "One day all will be as you have seen it there, in Wirikuta. The First People will come back. The fields will be pure and crystalline, all this is not clear to me, but in five more years I will know it, through more revelations. The world will end, and the unity will be here again. But only for pure Huichol."

Among the Tarahumara, the Peyote cult is less important. Many buy their supplies of the cactus, usually from Huichol. Although the two tribes live several hundred miles apart and are not closely related, they share the same name for Peyote - Hikuri - and the two cults have many points of resemblance.

The Tarahumara Peyote dance may be held at any time during the year for health, tribal prosperity, or for simple worship. It is sometimes incorporated into other established festivals. The principal part of the ceremony consists of dances and prayers followed by a day of feasting. Oak and pine logs are dragged in for a fire and oriented in an east-west direction. The Tarahumara name for the dance means "moving about the fire", and except for Peyote itself, the fire is the most important element.

The leader has several women assistants who prepare the Hikuri plants for use, grinding the fresh cacti on a metate, being careful not to lose one drop of the resulting liquid. An assistant catches all liquid in a gourd, even the water used to wash the metate. The leader sits west of the fire, and a cross may be erected opposite him. In front of the leader, a small hole is dug into which he may spit. A Peyote may be set before him on its side or inserted into a root-shaped hole bored in the ground. He inverts half a gourd over the Peyote, turning it to scratch a circle in the earth around the cactus. Removing the gourd temporarily, he draws a cross in the dust to represent the world, thereupon replacing the gourd. This apparatus serves as a resonator for the rasping stick: Peyote is set under the resonator, since it enjoys the sound.

Incense from burning copal is then offered to the cross. After facing east, kneeling, and crossing themselves, the leader's assistants are given deer-hoof rattles or bells to shake during the dance.

The ground-up Peyote is kept in a pot or crock near the cross and is served in a gourd by an assistant: he makes three rounds of the fire if carrying it to an ordinary participant. All the songs praise Peyote for its protection of the tribe and for its "beautiful intoxication".

As with the Huichol, healing ceremonies are often carried out. The Tarahumara leader cures at daybreak. He first terminates dancing by giving three raps. He rises, accompanied by a young assistant, and circling the patio, he touches every forehead with water. He touches the patient thrice, and placing his stick to the patient's head, he rasps three times. The dust produced by the rasping, even though infinitesimal, is a powerful health- and life-giver and is saved for medicinal use.

The final ritual sends Peyote home. The leader reaches toward the rising sun and rasps thrice. "In the early morning, Hikuli had come from San Ignacio and from Satapolio riding on beautiful green doves, to feast with the Tarahumara at the end of the dance when the people sacrifice food and eat and drink. Having bestowed his blessings, Hikuli forms himself into a ball and flies to his shelter at the time."

Peyote is employed as a religious sacrament among more than forty American Indian tribes in many parts of the United States and western Canada. Because of its wide use, Peyote early attracted the attention of scientists and legislators and engendered heated and, unfortunately, often irresponsible opposition to its free use in American Indian ceremonies.

It was the Kiowa and Comanche Indians, apparently, who in visits to a native group in northern Mexico, first learned of this sacred American plant. Indians in the United States had been restricted to reservations by the last half of the nineteenth century, and much of their cultural heritage was disintegrating and disappearing. Faced with this disastrous inevitability, a number of Indian leaders, especially from tribes re-located in Oklahoma, began actively to spread a new kind of Peyote cult adapted to the needs of the more advanced Indian groups of the United States.

The Kiowa and Comanche were apparently the most active proponents of the new religion. Today it is the Kiowa-Comanche type of Peyote ceremony that, with slight modifications, prevails north of the Mexican border. This ceremony, to judge from the rapid spread of the new Peyote religion, must have appealed strongly to the Plains tribes and later to other groups.

Success in spreading the new Peyote cult resulted in strong opposition to its practice from missionary and local governmental groups. The ferocity of this opposition often led local governments to enact repressive legislation, in spite of overwhelming scientific opinion that Indians should be permitted to use Peyote in religious practices. In an attempt to protect their rights to free religious activity, American Indians organised the Peyote cult into a legally recognised religious group, the Native American Church. This religious movement, unknown in the United States before 1885, numbered 13,300 members in 1922. Membership of the Native American Church at the present time is claimed to be a quarter of a million Indians.

Indians of the United States, living far from the natural area of Peyote, must use the dried top of the cactus, the so-called mescal button, legally acquired either by collection or purchase and distribution through the United States postal services. Some American Indians still send pilgrims to gather the cactus in the fields, but most tribal groups in the United States must procure their supplies by purchase and mail.

A member may hold a meeting in gratitude for the recovery of health, the safe return from a voyage, or the success of a Peyote pilgrimage: it may be held to celebrate the birth of a baby, to name a child, on the first four birthdays of a child, for doctoring, or even for general thanksgiving. The Kickapoo held a Peyote service for the dead, and the body of the deceased is brought into the ceremonial teepee. The Kiowa may have five services at Easter, four at Christmas and Thanksgiving, six at New Year. Especially among the Kiowa, meetings are held only on Saturday night. Anyone who is a member of the Peyote cult may be a leader or "roadman". There are certain taboos which the roadman, and sometimes all participants, must observe. The older men refrain from eating salt the day before and after a meeting, and they may not bathe for several days following a Peyote service. There seem to be no sexual taboos, as in the Mexican tribes, and the ceremony is free of licentiousness. Women are admitted to meetings to eat Peyote and to pray, but they do not usually participate in the singing and drumming. After the age of ten, children may attend meetings but do not take part until they are adults.

Peyote ceremonies differ from tribe to tribe. The typical Plains Indian service takes place usually in a teepee erected over a carefully made altar of earth or clay; the teepee is taken down as soon as the all-night ceremony is over. Some tribes hold the ceremony in a wooden round-house with a permanent altar of cement inside, and the Osage and Quapaw Indians often have electrically lighted round-houses.

The Father Peyote (a large "mescal button" or dried top of the Peyote plant) is placed on a cross or rosette of sage leaves at the center of the altar. This crescent-shaped altar, symbol of the spirit of Peyote, is never taken from the altar during the ceremony. As soon as the Father Peyote has been put in place, all talking stops, and all eyes are directed toward the altar.

Tobacco and corn shuck or blackjack oak leaves are passed around the circle of worshippers, each making a cigarette for use during the leader's opening prayer. The next procedure involves purification of the bag of mescal buttons in cedar incense. Following this blessing, the roadman takes four mescal buttons from the bag which is then passed around in a clockwise direction, each worshipper taking four. More Peyote may be called for at any time during the ceremony, the amount consumed being left to personal discretion. Some peyotists eat up to thirty-six buttons a night, and some boast of having ingested upwards of fifty. An average amount is probably twelve.

Singing starts with the roadman, the initial song always being the same, sung or chanted in a high nasal tone. Translated, the song means: "May the gods bless me, help me, and give me power and understanding."

Sometimes, the roadman may be asked to treat a patient. This procedure varies in form. The curing ritual is almost always simple, consisting of praying and frequent use of the sign of the cross.

Peyote eaten in ceremony has assumed the role of a sacrament in part because of its biological activity: the sense of well-being that it induces and the psychological effects (the chief of which is the kaleidoscopic play of richly colored visions) often experienced by those who indulge in its use. Peyote is considered sacred by native Americans, a divine "messenger" enabling the individual to communicate with God without the medium of a priest. It is an earthly representative of God to many peyotists. "God told the Delawares to do good even before He sent Christ to the whites who killed him…" an Indian explained to an anthropologist. "God made Peyote. It is His power. It is the power of Jesus. Jesus came afterwards on this earth, after Peyote…. God (through Peyote) told the Delawares the same things that Jesus told the whites."

Correlated with its use as a religious sacrament is its presumed value as a medicine. Some Indians claim that, if Peyote is used correctly, all other medicines are superfluous. Its supposed curative properties are responsible probably more than any other attribute for the rapid diffusion of the Peyote cult in the United States.

The Peyote religion is a medico-religious cult. In considering native American medicines, one must always bear in mind the difference between the aboriginal concept of a medicinal agent and that of our modern Western medicine. Primitive societies, in general, cannot conceive of natural death or illness but believe that they are due to supernatural interference. There are two types of "medicines": those with purely physical effects (i.e., to relieve toothache or digestive upsets); and the medicines, "par excellence", that put the medicine man into communication, through a variety of hallucinations, with the malevolent spirits that cause illness and death.

The factors responsible for the rapid growth and tenacity of the Peyote religion in the United States are many and interrelated. Among the most obvious, however, and those most often cited, are: the ease of legally obtaining supplies of the hallucinogen; lack of federal restraint; cessation of intertribal warfare; reservation life with consequent intermarriage and peaceful exchange of social and religious ideas; ease of transportation and postal communication; and the general attitude of resignation toward encroaching Western culture.

PEYOTE HOTLINKS